Now that you’re an Internet publisher, you may look at advertising in an entirely different light from when you were just an Internet user. Users are seldom big fans of ads. But as a publisher, you not only want to draw readers for your content, you also may need to raise money to keep your operations going.

Let’s take a look at the various types and uses of advertising online.

General Research on Ads

- They’re not well-loved. Much research has been done about ads. Jakob Nielsen, who for many years has been publishing usability advice and research at useit.com, long ago established a clear truth: People don’t like ads online. A recent column, “The Most Hated Advertising Techniques,” outlines many of the issues.

- They’re not well-viewed. Internet surfers have developed a fairly foolproof method for avoiding bothersome ads: They don’t look at them. An EyeTrack study by The Poynter Institute has a number of observations about this phenomenon.

In a nutshell, Internet users have learned to recognize the usual size, placement and design of advertisements and simply ignore them.

It’s possible to get around this by using non-standard ad sizes and placements or interactive ads – but this requires that you work with your advertisers to customize their ads for your site. The results could also interfere with your site’s navigation or design.

Smart advertising aims to get around both these issues while also respecting the important distinction between editorial content and advertising.

Ad Placement

There are two schools of thought on ad placement. One says: Run many ads to maximize advertiser exposure and give users many choices to see something that interests them. Usually these ads are scattered so that there’s no “safe harbor” for the eye to avoid them.

The other school of thought advocates placing fewer ads – as few as one per page – and making each one count, giving it a high degree of visual isolation and prominence.

Your ad strategy will depend on how you intend for people to use your site. If you want them to be comfortable and pleased with the site and visit often, ad “carpet-bombing” is probably not the way to go.

If you expect your site to host a broad audience of one-time visitors, multiple ads might make more sense.

Generally, it’s better to have smaller, quicker-loading pages with specific bits of information – single short articles, for example. Smaller, shorter items lead to better search engine rankings and traffic. On this sort of site, using five ads with a three-paragraph story wouldn’t make sense. Combining quicker-loading pages with shorter items and fewer ads is a best-case scenario for users as well as advertisers.

Pop-up ads

Pop-up ads appear in a new window when the user enters or exits a web page. Pop-under ads open up, then sink below the active window, leaving the ad behind when the original window is closed. Both use the same underlying technologies. Besides being voted among the most irritating technologies on the web, pop-up ads are losing their reach these days because of ubiquitous pop-up blockers.

Safari, Opera, Firefox, Netscape and Camino all offer pop-up blocking. Earthlink and AOL have pop-up blocking technology (although AOL lets its own pop-up ads through). The Google and Yahoo toolbars, among others, offer pop-up blocking as a preference.

In general, avoid creating ads that open new windows unless it solves a technical problem, such as server load. Even then, try twice as hard to solve it without a pop-up. Regular users are simply too prone to disable, or automatically close, pop-up windows.

Ad Sizes

There are still no guarantees of specific ad sizes in the online world, but most major sites offer at least a subset of the types of ads recommended by the Internet Advertising Bureau. They list 16standard ad sizes, from 88×31 to 300×600.

The list covers several basic types of ad sizes:

- Banners (short, wide rectangles).

- Skyscrapers (narrow, tall rectangles).

- Buttons (small squares of various dimensions).

Banners are the most common, tracing their size all the way back to 1994, and thus are often the most ignored by site users.

From a designer’s perspective, banner ads are hardest to squeeze in after the page layout is set. Vertical ad spaces are commonly the easiest to modify or increase – three 120 x 90 ads instead of a 120 x 240, for example.

Larger ads are harder to ignore, and The Poynter Eyetrack study observes that advertising within a story is harder to ignore. (The New York Times and CNet both were early adopters of the half page ad, which takes up a large amount of visual space and can be difficult to fit within a standard three-column layout.

Ad Types

The earliest banner ads were strictly GIFs or JPGs. When animated GIFs first were supported in Netscape 2.02, an epidemic of blinking, flashing ads followed. However, larger, more complex animations were hard to download. A new technology, Flash, came along and offered not just smoother animations with smaller file sizes but also the option to add sound and video.

Advertisers tried more and more ways to attract attention to the banner space; some even included small games or interactive experiences using Java. Ultimately, though, web users filtered out these efforts and click-through rates dropped.

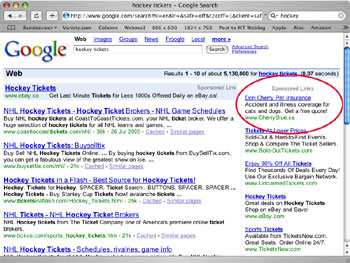

Advertising seemed destined to become more and more obtrusive. Then, in February 2002, Google introduced a text ad program and succeeded in getting a significant slice of the online advertising market. Its simple text-based links proved to get as good, if not better, clickthroughs than garish flash ads.

Let’s examine each ad type in detail.

Images

Most banner ads are images, in JPG or GIF formats. Of course, animated images are popular with advertisers who want to draw attention to their message or who have more to say than can fit into a static ad.

Animated ads can easily become too large to download quickly, though, so it’s best to tell advertisers that there’s a limit to the file size of ads on the site. A realistic limit is 15K for the standard banner.

A single animated ad might not be too distracting, but a whole row of them could be overkill. Consider limiting, or charging a premium, for the use of animated ads.

For more examples, see webdevelopersnotes.com.

Text

For content-rich sites, text-only ads have a good rate of visibility and interaction. Google, when it launched its ad program, only offered advertisers the option to place text ads. This ensured compatibility with the widest audience and was also simple for advertisers to set up.

For the content site, consider a box of plain text ads – something relevant from the classifieds, displayed on an article page, for example.

These ads, with specific bits of information contextually relevant to the site’s audience, tend to get the best click-through rates of any current ad types. It is unlikely, though, that they have much branding value. As such, they’re best recommended to smaller advertisers who have a specific action they want their ad to accomplish as opposed to a bigger company that wants to get its name out there.

Flash and Java

Flash is a specific software program from Macromedia that allows complex animation techniques in a fast-downloading package. Almost all browsers can display Flash files, though advanced Flash options may cause problems in some browsers.

With Flash, advertisers can add sound, full-motion video, interactivity and other features to ads. Whether this will increase the ad’s effectiveness depends on the context and content of the ad.

(To see several excellent examples, click here)

Java is another technology that can be used to craft ads. Java-based ads are rather tricky to set up, but they can add some interesting effects even beyond those of Flash. Imagine an ad that allows readers to send an SMS message or take a picture with a webcam and post it online. That’s the sort of flexibility Java can lend to an ad. It’s unlikely you’ll be making Java ads, but you may be asked if your ad software can handle serving them. Let’s take a look at software solutions next.

Ad Software and Services

At its very basic, ad software does two things:

- It keeps track of what ads are put on which pages of your website.

- It keeps track of how many times those ads are clicked on.

Full service

At the expensive end of the spectrum are the big ad-serving companies. They make it easy for the site administrator or sales person to upload ads and schedule them to be displayed to certain types of viewers, for a certain number of times, during certain days or hours, or until a certain number of clicks are reached. Some examples of these include:

These players all tend to have certain minimum fees and might have a lot more power than a start-up site needs. It’s nice to know they exist, however, as your site’s traffic grows.

Install it yourself

At the cheapest end of the scale, open-source software program OpenX (formerly PhpAdsNew) is a free ad-tracking system that you can install yourself.

Google AdSense

For those who would like someone else to handle the sales and ad selection, they can sign up for Google’s AdSense program. With AdSense, the content site merely reserves a spot on each of its web pages, and Google fills it with advertisers whose content it determines matches the editorial content of the page.

The ad placement is inexact but close to the mark in most cases. There’s no worry about selling ads or collecting payment; Google pays your organization based on how many people click on the Google ads on your site.

Ad Payment Models

Over time, there have been several payment models for web advertising.

Per view

Initially, a flat rate or pay-per-impression model prevailed. If a site shows 1,000 pages with a given ad, the advertiser would pay a few cents per page. This is called a CPM deal, for cost per thousand. (The name comes about because M is the Roman numeral for 1,000). Although there is still occasional debate over the point at which an ad is considered “viewed,” this model remains the most common and most stable.

Per click

Advertisers realized, though, that they could pay based on another metric: the click. A pay-per-click (also called CPC – cost per click) model soon arose, where advertisers paid more but only for each time a reader clicked on an ad.

Affiliate / conversion

Advertisers also realized that they could pay based on yet another metric because of the Internet’s ability to track users. They could pay based on “conversion” – that is, whether a person sent to their site actually bought something. This is the riskiest for the content provider for two reasons:

- It’s out of the content provider’s control whether the advertiser is going to successfully convince a person to buy once a person gets sent to their site. If the advertiser doesn’t make a sale, the content site won’t get paid.

- Also, it’s possible for the content site to track the ad exposures and the clicks but not the conversions. So the content site gets paid whatever the advertiser says is its share.

Nevertheless, affiliate relationships can be quite profitable for both sides, so they shouldn’t be dismissed.

It’s easy to sign up for many affiliate programs. Amazon.com and Linkshare are probably the two most prominent ones. Both give a return on any products sold through the participant’s website. Of course, any ethical website owner would want to make any relationship with an affiliate clear to users.

Depending on the nature of your site, it also may be important to steer clear of giving your users any impression that an affiliate arrangement biases your content in any way.